27 Jun China Screenwriters: How to Write for Hollywood

China screenwriters looking to expand their reach should consider writing for Hollywood.

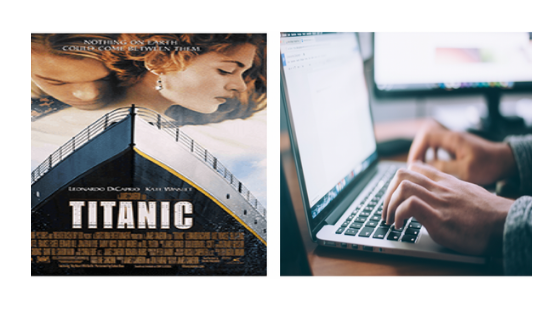

Today’s blog is for China screenwriters to understand American screenplay structure and how to write for Hollywood.. A popular and easy guide to American screenplay structure is the book Saving The Cat by Blake Snyder. I did a side by side comparison of the book’s plot points to a movie many Chinese audiences know and love – Titanic.

HOW ARE CHINESE SCREENPLAYS DIFFERENT FROM HOLLYWOOD’S?

In the Variety article Huayi Brothers Pictures CEO Jerry Ye highlighted the differences between China and the West when it comes to screenwriting. He said, “The thing with China right now is that there’s a huge lack of creative power… So we spend a huge amount of time finding a good script…. In many countries, there are loads of great scripts and stories sitting around, but no capital or market to support them. It’s the opposite in China.” China screenwriters, learn American structure and you can expand your market.

A big distinction is in China – the screenwriting system serves the director. In Hollywood, the producer is developing the script, not the director. Wanda Media GM Jiang Wei (aka Wayne Jiang) added “Chinese writers…would often fail to execute what he’d asked of them, and turn in scripts that veered too far away from the company or the director’s original vision. But when working on Hollywood films he saw that writers were used to doing multiple iterations of the same story without touching its overall direction or main storyline. And Hollywood writers were used to discussing what elements they’d like to add before going ahead with them.”

So let’s begin with basic American screenplay structure with illustrations from the film Titanic. Note that the page numbers below correspond to a typical 110-page screenplay. They do not correspond to the film since that was a three-hour movie.

ACT ONE

Opening Image

(Page 1): This is a snapshot of the hero’s ordinary world before the hero’s adventure, begins. Often the opening image mirrors the Closing Image.

TITANIC: Old film clips show the Titanic setting sail. The irony of happy travelers waving goodbye on the deck clashes with the next shot. We move to modern times where a mini-submarine finds the wreck of the ship at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean.

Set up

(Pages 1-10): We see the hero’s ordinary world and what is missing in her life. We also learn about her problem that needs fixing over the story. In Act 1, the hero is in “stasis” – a period of inactivity. Stasis equals death. This means the “before” life of the hero – if it stays the same – then the protagonist will figuratively die.

TITANIC: We met Rose and learn she is being forced into a marriage to a rich man she dislikes, Cal. Her goal is to come to terms with her arranged marriage.

Theme stated

(Page 5): This is the message of truth you want the audience to come away with by the end of the movie. I believe the theme of this film is love is a powerful force beyond our imagination – more powerful than material wealth.

TITANIC: The thematic question that Rose must answer is – is security better than true love? Her mother tells her they are penniless and she must marry her fiancé, Cal.

Catalyst (Page 12): AKA – the inciting incident. The hero is presented with an opportunity to go on an adventure. She can’t go back to the “before” world. Change has begun.

TITANIC: Over dinner with the snobby upper-class passengers, Rose has a sudden realization of how the rest of her life will play out. Rose’s mother and her overbearing fiancé put down Jack and his commoner life. This pushes Rose to run to the back of the ship to commit suicide by jumping overboard.

Jack shows up and attempts to convince Rose that jumping into the Atlantic Ocean is a horribly bad idea. Rose must choose between her terrible life, and taking the advice of this charming but penniless stranger.

Debate

(Pages 12-25): The hero is afraid of change and wants to go back to her old life – to stasis. Often the hero refuses the call to adventure.

TITANIC: Rose’s mother tells her they are broke and need Cal’s money to survive. Cal gives Rose a huge diamond necklace but it’s clear she doesn’t love him. Rose lies to Jack and tells him she loves Cal and not to worry about her.

Break into Two

(Page 25): Here the hero crosses the threshold. She makes a choice to go on the journey. She leaves the ‘thesis world” (what the hero’s flawed view is) and enters the “anti-thesis” world of act two.

TITANIC: Rose sees a rich mother instructing her daughter in upper-class ways. Rose realizes this ritual is all life will ever give her. Rose changes her mind and comes to Jack. She begins a relationship with Jack.

Note – if you want to write for Hollywood – a good bet is to write a female-led film which is growing in popularity. See my previous blog Why Female-Led Films Make More Money At The Box Office and Sex, Lies & Why We need Female-Led Films

ACT 2

B Story

(Page 30): Usually a romantic subplot – often called the “B” story” is introduced. Usually the love interest and hero will debate about the theme – the truth or message you hope to convey by the end of the movie.

TITANIC: Here we see scenes about Rose and Jack’s growing love for each other and her growing problems with Cal and her mother.

Fun and Games

(Pages 30-55): This is the first half of Act 2. Here the hero explores the new world and overcomes many obstacles

TITANIC: Jack invites Rose to the steerage, third class section of the ship where third-class passengers are enjoying a lively dance.

Midpoint

(Page 55): Now is the time for a huge plot twist that raises the stakes. The hero must recommit to the new goal. Here the hero decides there is no turning back. Often the “B” story will cause this midpoint plot twist.

TITANIC: Cal berates Rose for dancing with Jack. He explodes in anger and flips over their breakfast table. He is determined to control Rose. Later, Jack sneaks into her room and confesses his feeling for her. Over lunch with the high society group, she sees how empty her future will be. She finds Jack. He gives her his “King of the World” treatment on the bow of the ship. She begins a love affair with Jack.

Rose shuns Cal. She poses for Jack -a penniless but talented artist. She poses in the nude wearing only the diamond necklace Cal gave her.

Bad Guys Close In

(Pages 55-75): Here you (the writer) throw seemingly insurmountable obstacles at the hero. The hero’s original plan fails. They are betrayed or their team is split up.

TITANIC: Rose and Jack make love. The ship hits an iceberg. Rose and Jack rush to warn her mother and Cal.

Cal frames Jack for the theft of the diamond necklace. Jack protests his innocence but Rose believes Jack is a thief. Jack is hauled away. Cal slaps Rose, demonstrating what their married life will be like. Time is running out. Cal, Rose, and her mother head for the lifeboats.

All Is Lost

(Page 75): The hero is at their lowest point. She loses everything. Often something or someone (i.e. an ideal, a belief, or a person) dies. But this death (physical or emotional) of something old makes way for something new to be born.

TITANIC: Cal lets slip that Jack won’t be getting on any lifeboat. Rose realizes Cal framed Jack for the theft. She jumps off the lifeboat. She’d rather face death with Jack than marry Cal.

Dark Night of the Soul

(Pages 75-85): The hero hits bottom. But she must hit rock bottom before she can pick herself up again. The hero’s character arc is complete. She finally understands the truth she could not see when she began this journey. Often this new information is delivered via the “B” story. This is where the hero decides – quit and go home or give it one more try.

TITANIC: Rose rescues Jack from the detention area but the ship is sinking fast. Jack gets her to a lifeboat but it will only take women and children. Jack convinces her to get on. She does and leaves Jack behind.

Break into Three

(Page 85): And here China screenwriters, thanks to the hero’s new idea, she tries again. The new information presents the final goal the hero must achieve to complete the journey.

Rose quickly has a change of heart. She jumps off the life boat onto a lower deck.

ACT 3

Finale

(Pages 85-110): China Screenwriters, take note the hero confronts the antagonist with new strength. Now she incorporates the theme into her fight. She now has the experience of the “A” story and context from the “B” story. She leaves behind the “anti-thesis” world and enters her new truth – the “synthesis” world. Her journey will be resolved.

TITANIC: The last of the lifeboats are gone. The decks are in chaos. Rose and Jack make their way to the stern of the ship knowing the ship will soon go under the waves. Jack pulls Rose up onto the railing just as the ship goes vertical.

The ship sinks. Jack pushes Rose onto a floating piece of wood. But only she can fit. He makes her promise she will survive. He sacrifices her life for her and dies. A rescue boat later finds Rose.

On a new ship, Rose honors her promise to not marry Cal. At the end of the film, Rose – an old woman is on the ship that found the resting place of the Titanic. She drops her diamond necklace overboard and watches it sink. When she drifts off to sleep in her cabin, she is surrounded by her photos that prove she lived a full and happy life.

Final Image

(Page 110): Opposite of the Opening image – proving visually the change that has occurred within the character.

TITANIC: Later asleep in bed, Rose either dies in her sleep or falls asleep (it’s not clear in the film). She is her younger self and is reunited with Jack and the other passengers on the Titanic. The other passengers applaud as Jack and Rose kiss. She has found eternal love.

American audiences are accustomed to this structure. Now I don’t advocate that you use a ‘paint by numbers’ approach to screenwriting. China screenwriters, your script should not be formulaic. But to attract an American audience you need a familiar structure like this one.

No Comments